Productivity and Innovation: To Be Found in Established Companies

On Monday, October 16, 2017, Nicolai Foss, Rodolfo Debenedetti Professor in Entrepreneurship, held his Lectio Inauguralis. Here is his Lectio, entitled A key gap in entrepreneurship research: Understanding the established entrepreneurial company.

Mr. Debenedetti, President Monti, Rector Verona, esteemed co-panelists, ladies and gentlemen, many thanks for the kind introduction. I am profoundly grateful for having been selected for this Chair.

The fact that Bocconi University has a Chair in entrepreneurship directly reflects the generosity of the benefactor, Mr. Carlo De Benedetti, who chose Bocconi to honor the memory of his father Rodolfo Debenedetti both as an individual and as a businessman. It also reflects the massive international popularity and influence of entrepreneurship research and teaching: All over the world there has been a surge in the number of endowed chairs, programs, funds donated to entrepreneurship research, journals devoted to the field, number of conferences, and new teaching initiatives in entrepreneurship.

The area is a very lively one with all sorts of debates, some of them reaching into areas where entrepreneurship traditionally has not been discussed, as witness, for example, work on "social" and "institutional entrepreneurship." It is an area that stays close to business practice and which has a great potential to inform practice and policy.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP AS A POLICY CONCERN

The surge of interest in entrepreneurship reflects the increasing real-world importance of the phenomenon and the attention that policy makers devote to it.

Around the mid-1970s observers suggested that "churn" was increasing in the US economy; for example, firms were increasingly moving in and out of industries. Churn has different components, but one of them is the founding of new companies-that is, what many would take to be the essence of entrepreneurship.

The share of employment shifted dramatically from large companies to smaller ones. For example, in 1970, the Fortune 500 companies accounted for 20% of US employment, but only 8,5% in 1996 (Carlsson, 1999). Firms were getting smaller.

Policy makers quickly took an interest, particularly when important work began to show that much productivity advance was caused by reshuffling of assets when firms collapsed, merged, started up, and so on (e.g., Foster, Haltiwanger & Krizan, 2006), and that innovation and entrepreneurship played a role in these processes.

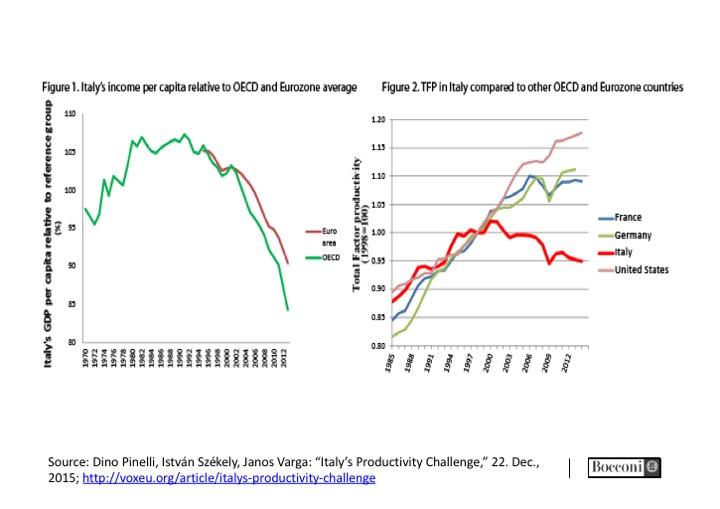

Entrepreneurship came to be seen as a means to fuel growth, not just in the US, but certainly also in a Europe plagued for a very long time now with sluggish productivity growth and relatively poor growth performance. Many here today are too familiar with the specific Italian challenges.

The Italian economy is only slowly returning to its pre-crisis levels of growth. Foreign investment remains low. It is tempting to link this to low levels of entrepreneurship and to certain features of the Italian economy that indicate that the climate is not optimal for entrepreneurship. Thus, in 2014, Italy registered the lowest level of venture capital investments as a share of GDP (0.002 percent) of any major European economy. The enterprise death rate is higher than the birth rate. Italy is currently ranked at number 45 on the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Index, and almost at the bottom in the EU. When it comes to contract enforcement, Italy is number 111 in the world, and again basically at the bottom in the EU.

It is not surprising, therefore, that there have been numerous calls, here and in other Western economies, for somehow stimulating entrepreneurship-both the supply of it and its quality-by designing policies and institutions that are conducive to entrepreneurship.

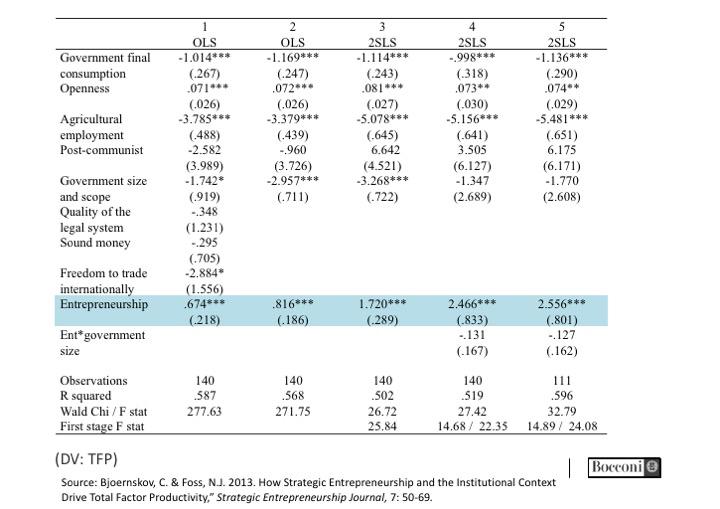

There is, of course, much theorizing and evidence that support the notion that entrepreneurship fosters growth. My own work with Christian Bjørnskov (e.g., Bjørnskov & Foss, 2008, 2012, 2013) looks at the impact of entrepreneurship on total factor productivity and on the role of institutions and policies in influencing this impact. Loosely, "total factor productivity" captures the production increases that cannot be traced to increasing the amounts of the traditional factors of production.

Bjørnskov and I argue that increases in total factor productivity result from new processes, new modes of organization, and better ways of managing. Such entrepreneurial experimentation with combining productive factors and trying these combinations out can take place more or less easily. If, for example, an economy is placed as no. 111 on the contract enforcement index, the entrepreneurial process is severely hampered. So, institutions matter.

We specifically argue that economic freedom is beneficial to the entrepreneurial process. So, the rule of law, well-defined and enforced property rights, easy regulations, low taxes, and limited government interference in the economy are good for entrepreneurship (Bjoernskov & Foss, 2008).

The specific mechanism we posit is that these institutions increase the so-called aggregate elasticity of substitution, an important mechanism in the growth process. They do this because the lower the transaction costs of engaging in entrepreneurship. The lower the transaction costs, the more beneficial experimental activity will take place. Resources will be allocated and reallocated to better uses. Growth results.

Bjoernskov build a unique panel data set consisting of 25 countries observed from 1980 to 2005 to test these ideas. We find that indeed entrepreneurship impacts total factor productivity.

Somewhat contrary to our expectations, we also find that increasing the active involvement of the government in the economy, as well as the tax burden, actually increases the impact of entrepreneurship on total factor productivity.

This can be interpreted in two different ways that we cannot really distinguish between, given our data. In one interpretation, entrepreneurship impacts strongly on productivity because entrepreneurship is facilitated by a large, well-functioning public sector. In another interpretation, all but the very most promising entrepreneurship initiatives are crushed by a huge and costly-to-run state apparatus.

This already suggests that thinking about public policies that may further entrepreneurship is not trivial. Let me continue along these lines.

On the basic level there is the whole issue if there should indeed be any specific policies aimed at increasing entrepreneurship. This is often taken as a given. There probably isn't a government anywhere in the Western world that doesn't promise to increase entrepreneurship in the economy. The current US administration is, for example, very big on this.

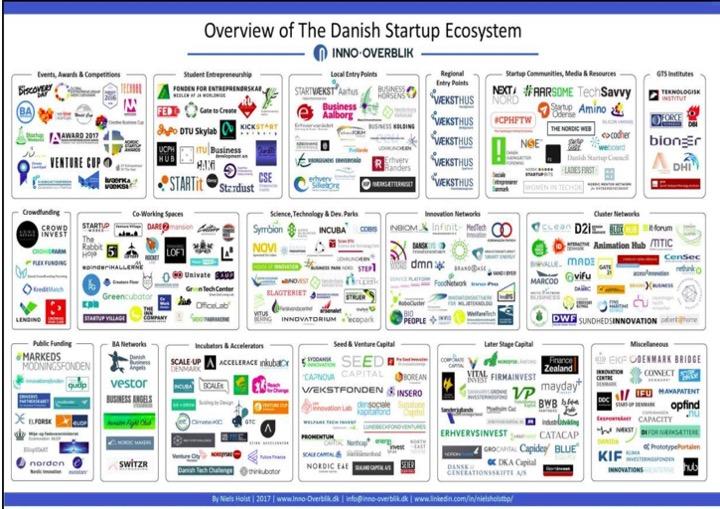

A much, much smaller country than the US, namely Denmark, is also very big on this. The following figure shows you the public infrastructure (or, jungle!) designed to support entrepreneurship in an economy with a population of 5,5 million people:

However, the case for using public funds to directly stimulate start-ups is actually not very strong. This is so for a number of reasons. First, productivity depends positively on firm age; start-ups simply aren't very productive. Second, how much start-ups actually account for in terms of job creation in the economy is still unclear; it may not be a lot. Third, government policies for entrepreneurship tend to create many jobs in highly competitive industries in which it is easy to get established. This means of course that such government policy also creates many failures (for more detail, see Shane, 2008).

Notice that I am not saying that we don't want entrepreneurship. Of course, we do, because some entrepreneurship results in the next Luxottica, Tenaris, Atlantia, .. or, Procter and Gamble, Microsoft, etc. That is, sometimes entrepreneurship leads to long-lived, large companies that continue for a long time to be innovative and entrepreneurial and often contribute massively to growth and job creation. This latter point seems to me to suggest that in thinking about entrepreneurship we also need to think about the already-established company.

THE START-UP BIAS IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP RESEARCH

Most entrepreneurship research deals with only a part of entrepreneurial activity in the economy, namely that represented by start-ups. Many scholars even define the study of entrepreneurship as the study of start-ups (e.g., Gartner & Carter, 2003: 196). Most of the economics of entrepreneurship, which is really a branch of labor economics, defines entrepreneurship as people self-employing by starting new ventures. Most of management research (as well as research in other parts of social science) takes a similar view.

Thus, scholars examine such questions as why do certain individuals, with certain traits and dispositions, start up firms, while others do not (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000)? What exactly are those traits and dispositions (Busenitz & Barney, 1997)? What are the relations in terms of knowledge overlap between the firm that used to employ the entrepreneur and the spin-off / start-up (Gompers, Lerner & Scharfstein, 2005)? Why is it that entrepreneurs need to start firms to realize business ideas (rather than just selling these to established firms) (Foss & Klein, 2012)?

This is all interesting. However, the view that the study of entrepreneurship only means the study of start-ups is unnecessarily constraining. It neglects the history of the entrepreneurship field, misrepresents the size and importance of entrepreneurial activity in the economy, and risks leading public policy astray.

Many of the greats of economics didn't take a narrow view of entrepreneurship as new firm formation. Thus, Jean-Baptiste Say (1803), one of the first economists to think seriously about the entrepreneur, described the entrepreneur as one who "shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield." Established companies surely do this.

My own work has stressed, building on the work of American economist Frank Knight (1921), that entrepreneurs creates value by imagining new uses of heterogeneous resources to service future customer/consumers wants under uncertainty and in the hope of profit (much of this is summarized in Foss & Klein, 2012). Because resources are heterogeneous, and it is not obvious which resources bundles "work," experimentation with resource bundles is often required. Because entrepreneurship is directed towards the non-yet-existing future, there are no objectively existing "opportunities." Because entrepreneurs are the ultimate decision-makers, they will hold residual decision rights, ownership, to key assets. In this view, which we call the "judgment-based view," there is no reason why such activities cannot take place in established companies. And, of course, they do. Entrepreneurship is a fundamentally about the exercise of effective stewardship of resources under uncertainty. Start-ups, self-employment, etc. are instances of this, but not the whole story.

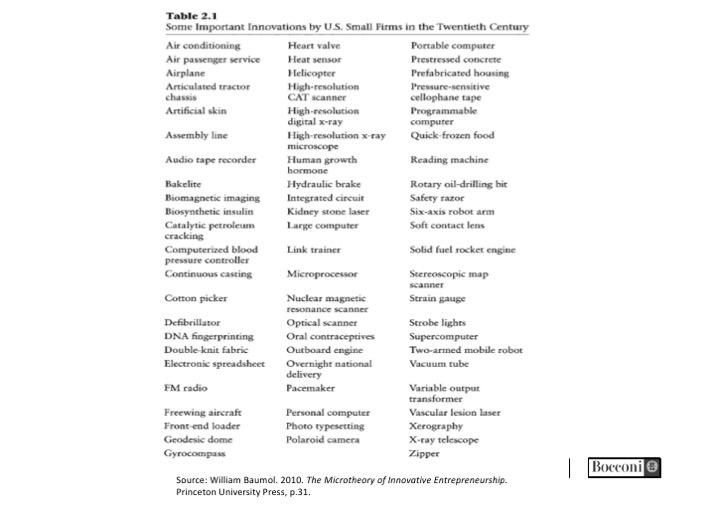

Perhaps the concentration on entrepreneurship as a start-up activity isn't so strange: The innovations pioneered by small upstarts are quite remarkable.

In fact, it seems to be taken for granted that there is a "small firm effect," that is, smaller firms, often upstarts, are disproportionally more entrepreneurial than larger firms (e.g., Elfenbein, Hamilton, & Zenger, 2012). This is partly motivated by much research on the relation between size and R&D, which suggests that R&D may be biased towards smaller firms. However, R&D is not the same as entrepreneurship (it is, of course, not even the same as innovation). Additionally, there is also a lot of folklore on how established companies have failed to innovate and be entrepreneurial.

Accordingly, much work on innovation essentially posits an entrepreneurial division of labor where small entrepreneurial firms supply the breakthrough innovations, but then have to ally with larger, established players that control complementary assets, like production, sales and marketing and so on.

One can understand the psychology of this-there is a pleasing David and Goliath quality to it (Baumol, 2010: Chapter 2)-, but are we sure the small firm effect stands up to scrutiny? Let's not forget that the innovations pioneered by larger, more established firms are also quite impressive.

But, we don't have strong empirical evidence that small, upstart firms are disproportionately more responsible for breakthrough innovations. In fact, it seems that we have stronger evidence for the exact opposite. I am thinking here of research by, for example, Bruce Tether (2008), who looks at SPRU data on innovations (which are biased towards more radical innovations) and find that the bigger companies matter relatively more. Another example is Chandy and Tellis' (2000) study of a large number of radical innovations in the consumer durables and office products categories which shows that there really isn't an "incumbent's curse."

The tendency to associate entrepreneurship narrowly with firm formation, and therefore with small firms, probably stems from Schumpeter. The focus of the early Schumpeter, the Schumpeter of The Theory of Economic Development (1911), is on start-ups. While the later Schumpeter (Schumpeter, 1942) focuses on the established firm as a driver of innovation, he also suggests that bureaucracy and routinization will increasingly make innovations mundane and trivial. Hence, the prevalent distinction between small, agile, entrepreneurial companies and large, established, sluggish companies.

The reason I touch on these details of the history of theory is, again, that we are saddled with an unfortunate historical legacy that leads us to under-emphasize the established company as an engine of entrepreneurship. This has to change.

UNDERSTANDING THE ENTREPRENEURIAL ESTABLISHED COMPANY

There are currently three biases that are hindrances when it comes to developing a theory of the entrepreneurial established company. I have already mentioned one of them, namely the prevalent definition of entrepreneurship as forming a new firm.

In addition, there is a tendency to over-concentrate on the act of the discovery of opportunities. Much research examines psychological, demographic or network-related factor as antecedents of opportunity discovery. An obvious advantage of this view, from the perspective of measurement, is that entrepreneurship is located at a point in time (i.e., that of the discovery of the opportunity).

However, entrepreneurship also involves complex processes of assembling bundles of complementary resources (Lippman & Rumelt, 2003), and coordinating actions and investments over time in the pursuit of profit under uncertainty (Casson & Wadeson, 2007). The processes by which entrepreneurial ideas are translated into actual actions, etc. too easily drop out of sight if the main emphasis is placed on discovery at a point of time and the antecedents of such discovery. Such processes typically involve many individuals whose efforts need to be coordinated.

However, there is also an over-concentration on single individuals in the literature. But, much entrepreneurship is, one way or the other, a team-based activity. Even if the recognition of an opportunity is inherently an individual act, evaluating and exploiting opportunities can certainly still be a team or more broadly firm activity.

So, research need to focus more on understanding entrepreneurship as a team activity, or at least one involving interdependent actions, within established company. This activity involves assembling necessary resources, perhaps adjusting entrepreneurial ambitions in the light of what resources are available, and coordinating those resources, actions, and investments. This brings attention to how this process is managed and organized-which unfortunately we know rather little about.

However, some of my own research has addressed this, looking at how decentralization, formalization, internal communication, and so on influence firm-level entrepreneurship (e.g., Foss, Laursen, & Pedersen, 2011; Foss, Lyngsie, & Zahra, 2013; Barney, Foss, & Lyngsie, 2017). And, there is also a fairly established research literature on intrapreneurship, corporate venturing, and intra-organizational ecology.

The basic model of this literature is an evolutionary one: New variation is introduced in a bottom-up manner, and the role of top-management is essentially reactive-to select among the variation that is generated at lower echelons of the company and identify the few good ideas in the mix. In fact, the tone of this literature is that direct top-manager involvement in the entrepreneurial process is directly counter-productive.

In a recent article with Jay Barney and Jacob Lyngsie, I empirically examine this received view. We match two datasets, one from a survey and one based on Danish register data. It involves about 170,000 individual level observations.

We are interested in the following: How do workforce diversity, bottom-up initiative, and top-manager involvement combine to influence the formation of entrepreneurial opportunities in established companies?

This is a pertinent question: Many firms deliberately seek to increase work force diversity (or utilize existing worforce diversity) and they seek to foster bottom-up initiative.

When we analyze the data, we do find that diversity and bottom-up initiative is positively associated with entrepreneurship (this is measured as the number of entrepreneurial opportunities over the last three years).

As usual, however, the really interesting stuff is in the interactions. When we interact diversity and bottom-up initiative with decision management from the top the impact on entrepreneurship goes up dramatically. The interpretation is that while increasing diversity and bottom-up initiative are associated with more entrepreneurship, carefully managing this process is vital! Contrary to the received view top managers actually amplify rather than reduce entrepreneurship at the firm level.

In some parallel work, also about "diversity", with Lyngsie, we look at whether there is a female leadership advantage in entrepreneurship in established companies (Lyngsie & Foss, 2017). We look at how having female managers in the upper echelons of established companies is related to firm level entrepreneurship. And, we find that having more than one female top-manager is associated with more entrepreneurship, in fact without limit (so firms that really want to be entrepreneurial shouldn't have any men in top management). However, we also find, rather interestingly and perhaps provocatively, that this effect is much weaker in companies that already have many women in the workforce!

CODA

My time is basically up now. What I have done in this brief talk is to develop a perhaps provocative theme-namely, that in research as well as policy we have been too focused on start-ups when it comes to understanding what entrepreneurship is and what entrepreneurship does.

Because of this lop-sided emphasis on the small, start-up company, we have neglected the established companies. However, these are certainly engines of entrepreneurship, productivity advances, most of the job creation, and growth. We neglect them at our peril.

Most of my research on entrepreneurship has been an attempt to tip the balance somewhat, in favor of the entrepreneurial established company. This is what I will continue doing here at Bocconi University.

I am very grateful for the support of Mr. Carlo De Benedetti, Rector Verona, and the wonderful colleagues at my department. So, to link to the next speaker, I hope to be able to fill an important structural hole here at Bocconi.