Private Spending Creates Poverty

The National Health Service was created to treat everyone, without distinction. But nowadays that universal promise is faltering: heavy prescription charges, drugs paid for by families, dental care largely excluded, and waiting lists that push people towards the private sector. The result? Already in 2022, 8.6% of families faced “catastrophic” healthcare expenses and 3.7% fell or returned below the poverty line after paying for medical care.

These are the figures from the World Health Organization report Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Italy, authored by Giovanni Fattore, full professor in the Department of Social and Political Sciences at Bocconi, and Luigi M. Preti, researcher at CERGAS at the same university. But the real news is that these figures hint to the future: without a significant increase in public spending, the proportion of families in financial difficulty due to healthcare costs will continue to grow until 2060.

“In the coming decades, without targeted investments, the right to health risks becoming a luxury,” warns Fattore. “Aging, commercial pressures toward unnecessary treatments, and stagnant public spending will inevitably push more families into health poverty.”

Where does the money go?

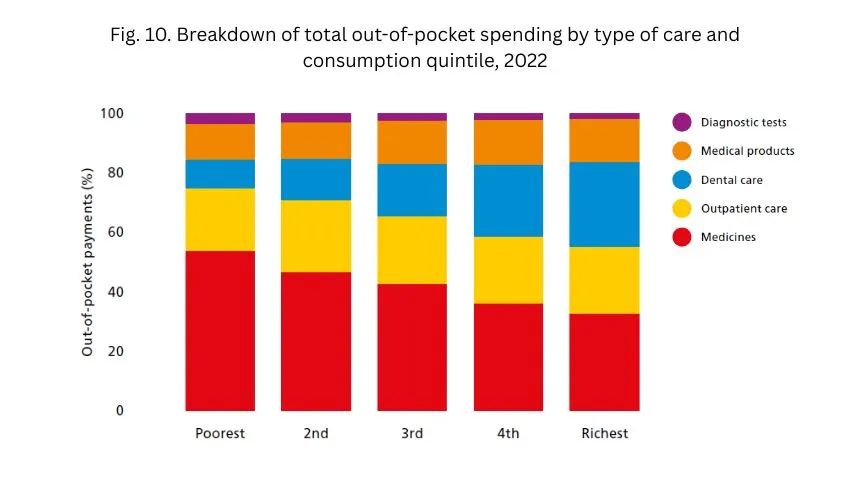

In 2022, 39% of private spending went to outpatient drugs, 23% to outpatient services, 22% to dentists, and 14% to medical devices. But the numbers change depending on income: the poorest spend mainly on drugs (54%), the richest on dentists (29%). For the most vulnerable families, catastrophic expenditure is driven by medicines and outpatient services; for the wealthiest, it is driven by dental care. The most disturbing thing about medicines is that one billion is spent on branded medicines when cheaper equivalents (generic) are available.

The concentration of spending is clear: in 2022, catastrophic spending hit 27% of the poorest households, 18% of households headed by economically inactive people, 13% of elderly people living alone, and 11% of households with two or more children.

And it will get worse: since 2025, copayments have increased by an average of 5.8%, with a stronger impact in the South. “Copayments do not protect those who have less,” explains Preti. “Without income-related caps and with strong regional disparities, we risk splitting the country in two as far as health care is concerned: one part where access is available, and one where it is denied.”

North and South: a widening gap

Fifty percent of families affected by catastrophic expenses live in the South, even though they account for less than 40% of the population. Here, the probability of becoming impoverished due to medical treatment is more than double that of the North. And healthcare mobility confirms this: in 2022, 72% of hospital patients “fleeing” to other regions involved patients from the South.

Europe-wide data paints an even grimmer picture: in 2022, Italy had a level of catastrophic healthcare expenditure above the EU average and higher than all Western European countries except Portugal. In 2023, out-of-pocket payments accounted for 23% of current healthcare expenditure, compared to 17% for the EU14 average and 19% for the EU27.

Public health expenditure in Italy (6.7% of GDP in 2022) remains lower than in almost all Western European countries, and in 2024 the share of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion was 23%, above the EU average (21%).

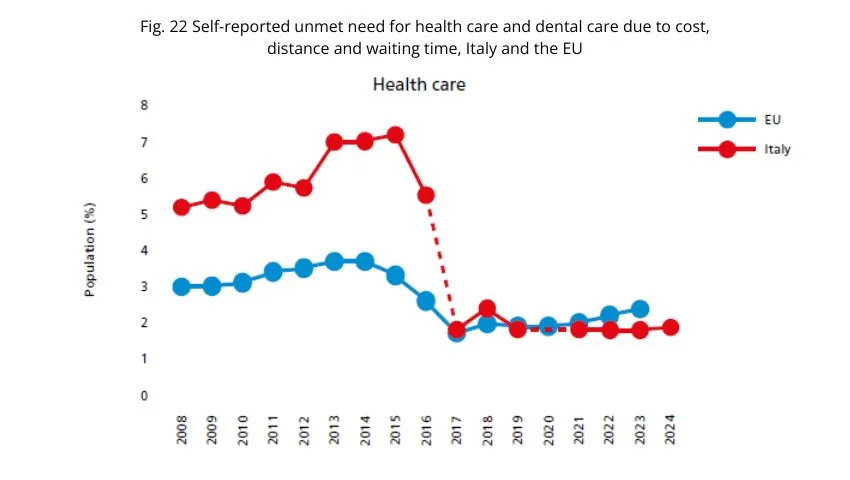

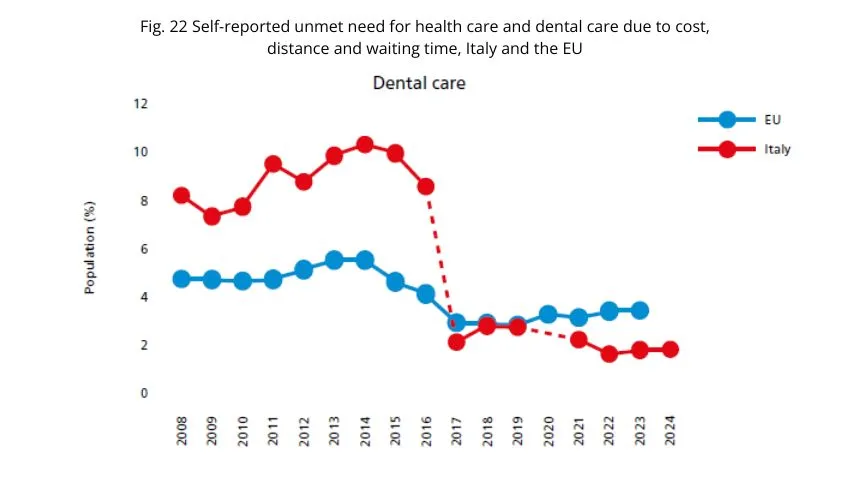

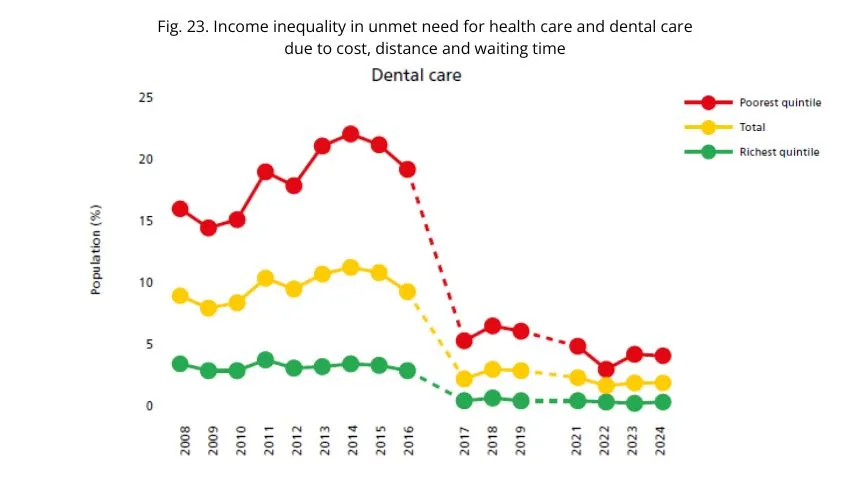

The unmet need

Economic hardship is compounded by access issues. Unmet need – i.e., the need for care that is not met – shows a significant income gap: lack of access is greater among the poor and reaches its highest levels in dental care, more than for health visits or prescription drugs.

WHO recommendations

The report calls for immediate action:

- introduce a nationwide cap on co-payments proportional to income;

- extend exemptions to all working-age people on low incomes;

- reduce 'avoidable co-payments' through greater use of generic drugs (currently only 9% of the market value in Italy, compared to the OECD average of 27%);

- expand public coverage for dental care and medical devices;

- cover travel costs for poorer patients who need treatment outside their home region;

- extend the right to National Health Service benefits to undocumented adult migrants.

The report also criticizes the 19% tax deduction on healthcare expenses over €129 per year, because it ends up favoring higher incomes.

Maria and Antonio live in Bari and have two teenage children. Both work, but their incomes are modest. When one of their children needs braces, the dentist's prospect exceeds €2,000. This is not covered by basic healthcare. They have to choose between paying in installments or cutting back on other family expenses. Meanwhile, Antonio pays €120 for an urgent ultrasound scan at a private clinic: otherwise, he would have had to wait three months. This is just one example, but it is a realistic one: already today, 48% of specialist visits are paid for entirely by patients.

If policies do not change, simulations show that by 2060 even a modest increase in private spending could push many more families into difficulty. An elderly couple in the south, with minimum pensions, could find themselves spending half their income on chronic medications, specialist visits, and medical devices. Without caps on copayments and with the north-south divide widening, those who have the means will continue to receive treatment, while the poor will have to go without.