Mario Biondi, the Writer Who Loves Technology

Curiosity and a desire to put himself on the line. This is how Mario Biondi explains how he was able to become an author who won the Super Campiello award in 1985, the first writer in the world to manage a personal website in 1995, a translator for four Nobel Laureates and even a sprinter, an Italian 4x100 relay champion who was chosen to compete with the National team in the late '50s.

He also explains his choice to attend Bocconi with curiosity and the desire to put himself on the line, as well as the belief that the humanities, the sciences and technical areas should be combined. He graduated from Bocconi in political economy in 1964, after completing classical lyceum with flying colors in Como. "It was a less obvious choice," he says, "but I was interested in the technical subjects of accounting and finance right away, while I had problems with mathematics taught by Giovanni Ricci, until the day when a classmate in the library explained very simply how a derivative is calculated. From that moment things changes to the point that I helped pay for my studies by tutoring math and I developed a real passion for statistics." At that time, Francesco Brambilla taught the subject and Biondi was always one of the first students to talk to the professor at the end of the lecture, having long collective discussions typical of the person. "But I chose Giovanni Demaria, the great representative of historiographic economics, to be my thesis advisor. At the time, however, historiographic economics was subsiding and giving way to new trends, such as Ferdinando di Fenizio's neo-Keynesian inclinations."

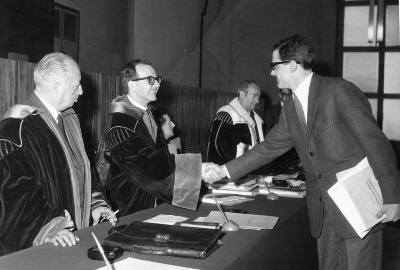

Biondi's graduation ceremony in the Aula Magna |

His interest in science and technology were not included in his thesis, but today the long-term effects can be seen. Biondi approached the internet when twenty users online in all of Milan were enough to overload the line and even today he deftly uses the language of html: while we talk, he fixes a little problem with one of the databases for Italian literature hosted on his site. Every morning he works on infinitestorie, the portal for the novel that he created for the Mauri Spagnol editorial group and which he has run since 2000. After graduation and a few attempts to stay at the University and do research, "I found a job at Nestlé," says Biondi, "but I felt first and foremost that I was a writer. I've kept everything I've written since I was 15 years old and I started going to Gruppo 63 meetings. Then I took advantage of the first opportunity to go to a publishing house, Einaudi, and then Sansoni, where I ended up becoming head of the press office." In later years, his work in the press office (first at Sansoni, then Longanesi) progressed in parallel with translations from English into Italian and the publication of poetry collections and the first two experimental novels. "I owe it to Mario Spagnol, who helped me move from experimental works to true novels," says Biondi. "And he helped motivate me to write Gli occhi di una donna, which was awarded the Super Campiello."For several years Biondi was considered a good luck translator. His first Nobel Laureate was Isaac Bashevis Singer. "He was a Longanesi author who I really loved, but in Italy he didn't have much commercial success. So I offered to translate Shosha almost for free based on my interest. After the first version of the translation, which was still temporary, the very next morning I heard the news of the Nobel Prize and the editor wanted to publish it right away. I found myself reading it over in a hurry, scribbling on the typescript while my secretary read the English version out loud. In the meantime, three copy editors took turns ripping the pages out of my hand to move on to the normal editing of the text for publication. I complained a little, but the publication of a Nobel Laureate seemed to be of vital importance for resolving the fates of a publishing house that at that time was in crisis, and the quick publication was inevitable..." His translations of William Golding and Wole Soyinka were also just before the awarding of the Nobel, while he translated The Black Book by Orhan Pamuk (from English into Italian and on the wishes expressed by the author), around fifteen years before the Prize. His curiosity and desire to put himself on the line led Biondi to not give in to the demands of the published world, which, after the success of Occhi di una donna, a historical novel, requested he take advantage of the trend. What followed, however, was La civetta sul comò, a detective story with a sense of humor, and Biondi then tried out a techno-thriller. "I work on my books like an architect," he explains, "I place the foundation, I construct a framework, the walls, I create characters starting from their past, using a lot of material that doesn't end up in the books, and then I make them interact."

Since 2003 his works have been travel memoirs and, in the meantime, works on digitalizing his writings. There are .epub, .mobi and .pdf versions of his novels on his computer, but has not yet decided what to do with them. "To sell them," he says, "I would have to create a business and become a small publisher, but I don't really want to. We shall see."