Innovation, History and Growth: a Nobel Prize Centered on Knowledge

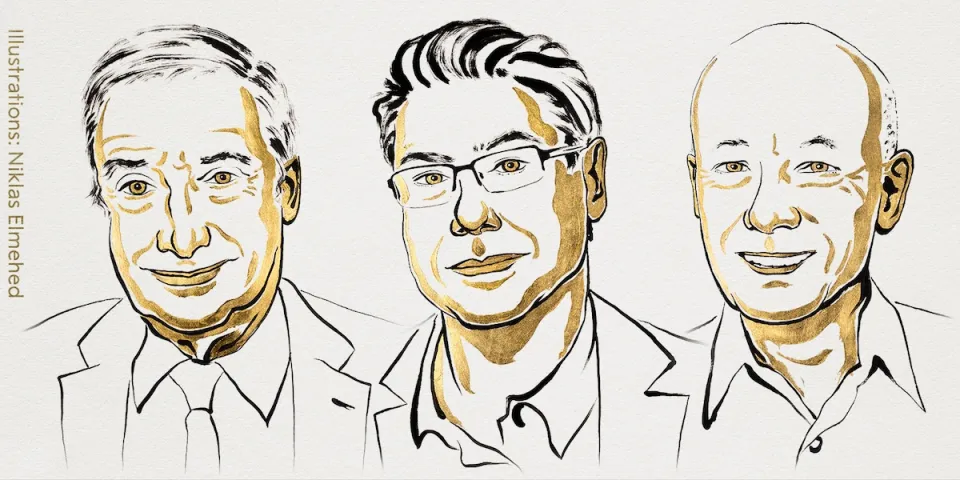

The Nobel Prize in Economics 2025 brings home a loud and clear concept: if you want to understand what really drives progress, you cannot ignore knowledge, research, and innovation. This year’s laureates are Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Joel Mokyr: a growth theorist, a mathematical modeler, and an economic historian.

“Aghion, Howitt and Mokyr have studied how and why knowledge and technological innovation are the foundations of economic growth,” notes Alfonso Gambardella full professor of Bocconi’s Department of Management and Technology and Co-director of the ION Management Science Lab at SDA Bocconi School of Management. Indeed, it is precisely in the union of the two lines of inquiry, the theoretical-model and the historical, that lies the extraordinary value of this trio.

The Theory of Engineered Creative Destruction

The core of Aghion and Howitt’s contribution lies in the formalization of the Schumpeterian theory of creative destruction, “that is, the continuous process whereby new technologies cause existing ones to become obsolete, pushing firms to innovate or succumb. In their view, economic growth is fueled by a virtuous spiral: competition spurs innovation, innovations beat previous technologies, this induces new competition, and so on. It is an intricate balance of risks, incentives and opportunities. “Growth,” Gambardella summarizes, “depends on a positive spiral in which, in competition, there are firms that innovate that are later outpaced by firms with even better innovations.”

Marta Prato, Assistant Professor in the Bocconi Department of Economics, also stresses the profound value of the three scholars’ research: “New technologies generate better products, more efficient production systems and a noticeable improvement in the quality of life. On the other hand, innovation also carries a destructive effect that can make previous innovations obsolete and put entire industries into crisis. This destructive force can result in job losses and hardships for workers tied to past technologies. Understanding both souls of innovation is crucial to designing growth policies that encourage technological progress while protecting those affected by it, promoting inclusive and sustainable growth."

The models derived from this approach are not abstract mathematical exercises: they provide insight into how public policies such as regulation, intellectual property protection, and research incentives can influence firms’ propensity to innovate. This is particularly relevant at a time when technology, artificial intelligence and climate change make us face radical challenges.

The historical perspective: Mokyr and the culture of innovation

But models alone are not enough. Enter then Joel Mokyr, an economic historian whose perspective restores depth to theoretical dynamics. Mokyr digs into the roots of change: how did cultures, tolerance, intellectual exchanges and institutions foster the emergence of scientific and technological progress?

Gambardella summarizes Mokyr's contribution as follows: “He identified diversity, tolerance and the free exchange of ideas, which matured in Europe on the eve of the Industrial Revolution, as the causes of progress in scientific research, knowledge and thus innovation and growth. An extremely timely discourse.” Marta Prato agrees that “Joel Mokyr's contribution highlights how a society’s innovative capacity is rooted in history, culture and institutions that value knowledge and scientific curiosity. Economic growth, then, is not only driven by technology, but also by a cultural context that values open-mindedness.” On closer inspection, then, Mokyr suggests that it is not enough to invest in research: we need a social and institutional context that allows ideas to circulate, to coalesce, to hybridize.

Bocconi and the new Nobel laureates: a dialogue that comes from afar

“This is a very well-deserved prize,” comments Guido Tabellini, economist and vice president of Bocconi. “Aghion and Howitt focused on the determinants of firms’ ability to innovate, developing theoretical models that were followed by empirical studies. Mokyr looked at the same issues from a historical perspective, studying the factors at the root of scientific and technological progress. All three were able to anticipate issues whose importance is recognized by all today.”

There is a personal and institutional relationship that binds the three Nobel laureates to Bocconi: Aghion was a visiting professor at Bocconi, and both Aghion and Mokyr participated in the Conference in Honor of Guido Tabellini. In addition, Tabellini co-authored with Mokyr the book Two Paths to Prosperity, which investigates how culture, institutions and social organization have led Europe and China along divergent paths over the long term.

Maristella Botticini and Mara Squicciarini (both professors in the Bocconi Department of Economics) were students of Joel Mokyr, and in particular, a study by Mara Squicciarini (with N. Voigtländer) is even cited in the Nobel Prize motivation: "Across Europe, Squicciarini and Voigtländer (2015) found that the Enlightenment reduced costs of accessing useful knowledge and influenced economic growth in 18th and 19th century France."