Nedo Fiano, the Importance of Remembering

When he comes to Bocconi on Wednesday 25 March to talk about his experience as an Auschwitz survivor (12:30pm, Aula Perego, Woe to Those Who Forget, with the President of the Italian Rabbi Assembly, Giuseppe Laras), it will be a return for Nedo Fiano. Born in 1925, Fiano is from a Jewish Florentine family and graduated from Bocconi with a degree in Language in 1968.

|

|

|

|

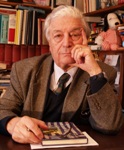

Nedo Fiano |

His book |

He was expelled from school at 13 years old when race laws were enacted in Italy and in 1944 Fiano was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where he arrived in May of that year. Immediately selected for an extermination camp and not a work camp, he was saved thanks to his knowledge of German, which his grandfather, who died in 1936, had taught him. When an SS first sergeant asked the Jews lined up to speak German, explains Fiano in A5405: The Courage to Live, the 2003 book in which he tells of his life at Auschwitz, he felt as if his grandfather had given him a push on the shoulder and he answered that he spoke German. He was assigned to a kommando that gathered deported prisoners from all over Europe in the camp and saw his grandmother arrive. Freed by the Americans in April 1945 at Buchenwald, where he was transferred by Germans on the run, Fiano weighed 37 kilograms and had just lost his entire family.

His studies at Bocconi from 1963 to 1968 were taken up to fulfill a promise he had made to his mother. "I studied while working, therefore attending class very little," he affirms today, "and when I showed up at university the other students, who were 20 years younger than me, waited to let me walk by, thinking I was a professor."

During those years Fiano didn't have a public image. He took up the duty of talking about the Holocaust and concentration camps only at the beginning of the '90s, when he began an activity of testimony throughout Italy. Since then, he has participated in 842 presentations. "At the beginning of the '90s nothing had happened in my public or private life that is connected to beginning this activity," tells Fiano. "Life does not have a linear flow. There is a natural barometer that suggests to anyone, from one day to the next, to write poetry, or to begin singing. I was convinced that I needed to talk about the Holocaust, in the hopes of provoking a reaction in young people that prevents its repetition. And then I felt like a traveler who feels like they have the last chance to catch a train that will never come again." As such, regularly speaking awarded him the Golden Ambrogino (an honorary medal awarded by the city of Milan) in 2008, while a decade earlier he was a consultant to Roberto Benigni for the film Life is Beautiful.

Fiano attributes most of the responsibility for the persecution of Jews to nationalized racism – first the Nazi and then the Fascist doctrine of race. "When the race laws were enacted," he reasons, "the Fascist regime had already instilled in the population a way of thinking and obeying that, at the beginning, even convinced quite a few Jews. My father supported the Fascist Party, and no one could see how it would end. I can't be too surprised, therefore, of my schoolmates' behavior, who did not hesitate in ostracizing me, for fear of their parents and the authorities. The fact that none of them came to look for me afterwards, however, saddens me."

Fiano, on the other hand, would rather tell about the horror that he lived through than explain it. "I don't try to understand the persecutors' behavior because I'm afraid that it would turn out to be a partial justification. I realize only that movements like the Nazi, Soviet and Fascist movements arise in moments of great crisis, when people feel the need for miracles on earth, and I'm afraid that our times share this characteristic with Weimar's Germany or Italy in the '20s."

After about ten years of only oral testimony and his first autobiographical book, Fiano returns to the reality of the Holocaust with a book, The Past Returns (Editrice Monti, 2009, 192 pages, 16 euros), which reflects the dry methods of his oral presentation. Juxtaposing squares that leave little space for emotion even in the narration of a dramatic event, the book tells the story of the choice of a Jewish couple from Turin, at the outbreak of the war, to entrust their newborn to a friend who lives in Switzerland and the recognition that follows him, 55 years later.