Middle-Aged Investors to the Rescue of US Stocks

In a period of extreme volatility in stock prices, it's interesting to look at markets under a more long-term perspective. Take US data, and consider the value in real terms (using the consumer price index as deflator) of a dollar invested in the stock market in 1900, with dividends being constantly reinvested. At the end of the millennium, the value of such investment would have grown by 800 times, according to the S&P index. It has since fallen, hovering around a multiple of 500 at the end of 2008. Are then we witnessing the end of a 100-year trend? A more careful analysis reveals a different picture: many generations have experienced radical fluctuations since the start of 20th century. $100 invested in 1951 would have grown to $600 twenty years later, but $100 invested in 1959 would have only grown to $160 two decades afterward (an average return of 2% p.a.). What then explains fluctuations in stock returns over a twenty-year horizon?

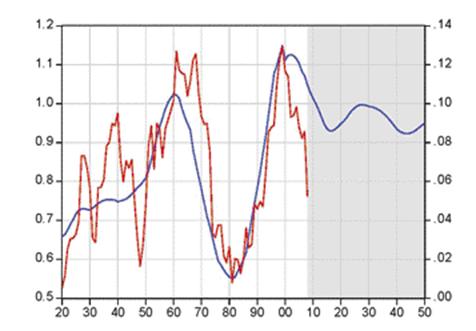

The graph below illustrates the idea. We plot 20-year returns against the MY variable, which is the US middle-to-young ratio, i.e. the number of people between 40 and 49 years of age divided by the number of people between 20 and 29 years of age. There is clear correlation between demographic fluctuations and MY projections until 2050 (from the US Census Bureau), and this calls for a certain qualified optimism over future prospects for stock investing.

What lies behind such statistical correlation? Geanakoplos, Magill and Quinzii ( "Demography and the Long Run Behavior of the Stock Market", 2004) provide an answer by considering an overlapping generations model which replicates demographic trends in the US. The three authors study a cyclical exchange economy where three generations alternate: agents borrow when they are young, invest in their middle age, and live off their investments when they are old. In such an economy the price-to-earning ratio (the long-run return of investing in stocks) is proportional to MY. A high level of MY pushes stock prices up, because flows of investments into stock prevail in the economy.

What lies behind such statistical correlation? Geanakoplos, Magill and Quinzii ( "Demography and the Long Run Behavior of the Stock Market", 2004) provide an answer by considering an overlapping generations model which replicates demographic trends in the US. The three authors study a cyclical exchange economy where three generations alternate: agents borrow when they are young, invest in their middle age, and live off their investments when they are old. In such an economy the price-to-earning ratio (the long-run return of investing in stocks) is proportional to MY. A high level of MY pushes stock prices up, because flows of investments into stock prevail in the economy.

In a recent work, Favero, Gozluklu and Tamoni ("Long-Run Factors and Fluctuations in the US Dividend-Price Ratio" 2009, IGIER, Department of Finance, Bocconi) analyze the empirical implications to the GMQ model, and econometrically identify the long-run equilibrium for the dividend-price ratio which is consistent with the empirical regularities portrayed in the graph. The three authors show how the equilibrium value is determined by MY and by a trend term that captures the impact of technology. As a consequence, demographic trends are very significant in forecasting stock returns over the medium-to-long period. The same demographic trends point toward an annual average real return of 8% for the stock market over the next twenty years.

This is good news, also because the crisis has bettered prospects for new investors entering the market today. This will be especially the case, if the demography of US stock investors keeps mirroring the demographic patterns of society at large.